A Political 'Street Fight' in Newark

By Ada Calhoun

February 28, 2006

Few cities in America are as rife with both corruption and civic pride as Newark, N.J. Documentary filmmaker Marshall Curry spent the 2002 election season absorbing plenty of both as he attempted to make a film about the candidates for mayor: the long-time incumbent, Sharpe James, and the 32-year-old upstart, Cory Booker.

Both are black, but James grew up poor while Booker was raised in the suburbs. James is an everyman making a six-figure salary; Booker is a golden boy living in the projects he's trying to revitalize. James' administration is notorious for corruption; Booker is as squeaky clean as they come. When James starts playing dirty -- spreading damaging lies about Booker, harassing Booker's supporters, even going after Curry -- the campaign turns brutal, turning the documentary into a thriller about how ugly the political machine can be.

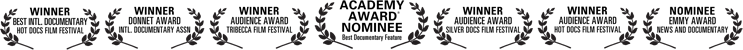

We spoke with Curry shortly after "Street Fight" (which showed on PBS and is now available on DVD) was nominated for the Best Documentary Feature Oscar.

Ada Calhoun: Congratulations on the Oscar nomination.

Marshall Curry: Thanks! The luncheon for nominees was fun. They put everybody together, so it's not just like the A-list movie stars at one table and the rest of us at the other table. Steven Spielberg was at the table next to me. Tim Burton was sitting to my left, and the guy that did the makeup for Narnia was sitting to my right.

AC: How do you rate your chances? You're up against March of the Penguins.

MC: Yeah, not great. Somebody said, "You think Sharpe James is tough, wait till you take on the penguins!"

AC: Has James seen the movie?

MC: I have to believe he has. The day after the PBS broadcast there was a mailing that went out around the city that basically equated me with Adolf Hitler. But they haven't contacted me directly. I know he's written a lot of crazy letters to PBS and anybody that gives the film publicity. He tries to breathe his fire on them. I think most of what he's doing is just kind of a Newark whisper campaign that attacks the film as propaganda.

AC: Judging from the film, he's great at those. He seems to take a page from our White House when it comes to disinformation.

MC: I think that's one of the reasons that people have been interested in the film. Most people don't care about Newark particularly. And they certainly don't care about some election that happened there a couple of years ago. But when we played in Amsterdam at a big documentary festival there, on our first night there were 600 people in the audience. And we've been selling it to European television and Latin American television, and I think the reason that those people are interested in it is that there is something about it that feels unfortunately familiar. Whether you're calling Cory Booker a white Jew or saying that John Kerry is a war criminal … it's amazing how these things work.

AC: How do candidates get away with such bad behavior?

MC: One thing that frustrated me so much in both the Newark election and the last presidential election is the mainstream media tries to cover elections in a way that they consider to be fair but that in fact is a distortion of reality. They try to say, "Well, George Bush said this, John Kerry said this" or "Cory Booker said this, Sharpe James said this." And they don't analyze whether one side is telling the truth. They just allow themselves to be mouthpieces for the two campaigns. And I think that they do that because that is what the audience assumes is fair. In fact, I think the media needs to be like a referee. A good referee doesn't call the same number of fouls on both sides; a good referee calls fouls when there are fouls.

AC: One expects malicious deception from Washington, but not necessarily from black Democrats in the Northeast.

MC: The Newark style of politics is in some ways left over from an earlier era. A lot of cities used to have machine-style politics: New York City's Tammany Hall, Daley's Chicago. Most places people have gotten rid of that by aggressive media scrutiny and an engaged citizenry. One of the reasons that I think Newark hasn't changed with the rest of the country is because it's so close to New York City it falls in this media shadow. New York just sucks up all of the scrutiny, all the television, all the newspapers, all the radio focused on New York politics, so Newark politicians can do whatever they want.

AC: But Newark's citizenry was entirely engaged. Ordinary people were getting in knockdown fights on the street with each other over their candidates. It's like the ultimate "Vote or Die" fantasy.

MC: That's a really interesting puzzle, isn't it? I mean, you're right; the people of Newark were very passionate about that election. On Election Day, the streets were buzzing with energy that New York definitely didn't have in the Ferrer-Bloomberg election. But there are two other dynamics in Newark that I think make it special: 1. people don't trust the local media very much. The Star-Ledger is the main newspaper and pretty much the only source of muckraking or news reporting. I guess there are a couple of radio stations as well. But, frankly, lots and lots of people just don't trust it. 2. People in Newark are very defensive about the city. It's been so maligned by comedians, newspeople, the country at large. You know, it's their home, it's where they live, it's where they grew up, and so it makes them think, "Well, that same media that's making fun of us is also telling us that Sharpe James is a bad mayor -- we don't trust one, so we don't trust the other."

AC: And he is very charming in his way. He seems to have that bulletproof local-politician charisma, like Marion Barry, or Buddy Cianci in Providence who -- what, at the very least kidnapped and tortured his ex-wife's boyfriend? It's amazing how much people are willing to forgive.

MC: I think that's exactly right. One of the things I really wanted the film to show is why Sharpe James won and why Cory Booker lost. There are a couple of scenes in particular where you see Sharpe just being a rascal. He's funny and he's charming, and he's got an incredibly compelling life story, and I think that carries a lot of weight. Again, not wanting to bring national politics into it too much, but the way people would talk in the last election was, which of these two guys is the one you'd rather sit down and have a beer with?

AC: Did you ever feel tempted to play campaign manager? You were seeing so much of what was going on, did you ever want to step in and …

MC: And say, "You guys should be doing this or doing that"? Yeah. There were points where I felt like, "Does anybody see this? They're making a mistake." I spent a lot of time just interviewing people on the streets. For instance, I had a sense that the accusation that Cory was a Republican was working in the streets when the campaign didn't think it was. I think they thought that it was such a ludicrous claim that they didn't even bother trying to refute it. I can remember talking to people and saying, "Who are you planning on voting for?" And they say, "Well, you know, I'm a Democrat so I guess I have to vote for Sharpe." But for the most part I knew that the more I got involved, the more people would suddenly become conscious of me as a guy with opinions, and I really wanted to just be a nondescript guy with a camera.

AC: At one point in the campaign a man on the Booker team is found at a strip club where an underage dancer is working, and that causes big problems. As you say, "If you run a choirboy campaign and you stumble, you fall hard."

MC: It's funny because Sharpe made it into a much bigger scandal himself, and what made it become a scene in the movie and what made it interesting was that Sharpe James went all around the city and would just hammer, hammer, hammer this issue until three weeks later or whenever it was, it came out that he had been to this place himself. But it gets to that choirboy thing. Cory runs on this platform of clean, good government, and also good personal ethics. He's a vegetarian, he doesn't drink, he doesn't smoke, he exercises. He's just this scrubbed-cheek ideal people have of who their son might turn out to be. And Sharpe James -- even the people who love him consider him a rascal. So when it came out that Sharpe had been to the club himself, I think everybody kind of just chuckled and said, "How 'bout that -- what a hypocrite. I can't believe he was there after saying that." But it did not fly in the face of who they thought Sharpe James was.

AC: I think Cory might remind people of Barak Obama.

MC: It's funny, I didn't know about Barak Obama when I was shooting the film. But when I was editing it, there was a big profile in The New Yorker , which was the first time I had even heard about him. And then some months later, I guess, he made the speech at the Democratic convention. And it was interesting because I had been editing one of the scenes where people are talking about this idea of whether you give up your blackness when you go to Stanford or Yale and, I don't know if you remember, but, in that speech Barak Obama attacked what he called "the slander that says that a black child with a book is somehow acting white." And I thought, "Wow, here's somebody saying this on the national stage, from a completely different state." It made me think that this issue that was being explored in Newark was not just a Newark issue. Cory was actually at the Democratic convention as well, giving a talk in one of the side rooms and somebody came up to him afterward and said, "Oh, you just are such an inspiration to this country, and I just think you're the greatest, and I look forward to voting for you for president when you decide to run one day, Mr. Obama." And he's like, "Oh, no. I'm the other one."

AC: Even though both James and Booker were both black, race became a huge issue in the campaign. Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton backed James. Cornel West and Spike Lee backed Booker.

MC: That was one of the things that I really felt was interesting about the whole thing. The media generally portrays the black community as monolithic. And to see an election where Al Sharpton and Jesse Jackson are on opposite sides from Cornel West and Spike Lee, that's just not something that people think about so much.

Then there was this question of racial authenticity. Sharpe essentially accused Cory of not being "authentically black," and raised the question, if your parents move to the suburbs, are they somehow giving up who they are racially? And I think most people, if you asked them that question, would say, "Oh, no. Of course not." But there still is something about that notion that has power with people. And frankly I don't think that it's just a black issue. I think people have notions about what it means to be Latino, Asian, or white, and that it would probably do us a lot of good to have people stop and think about what those characteristics are that we associate with race, and challenge them, because I think that most of the time they are pretty flimsy.

AC: How was it for you, not being black, to be so involved in this discussion?

MC: I expected that it would be much more of a challenge then it was. I thought people would be reluctant to talk about it with me. But one of the great things about Newark is that the people there are pretty upfront with you about what they think and how they feel about things, and so for a documentary filmmaker, it's a great place to make a film.

View on AlterNet's website

Back to Press

© 2012 Marshall Curry Productions. All rights reserved.