![]()

Documentary on Newark mayoral race wins prize at New York festival

By Steve Kornacki

May 1, 2005

First things first: PoliticsNJ.com does make a cameo appearance in Street Fight, the documentary about the 2002 Newark mayoral race that premiered this weekend at the Tribeca Film Festival. In one of the 82-minute film's pivotal moments Cory Booker's aides huddle in their election night headquarters scavenging for fresh data, the browser of their computer clearly set to this site's web address.

Granted it would take a PoliticsNJ.com employee to notice, let alone look for, such an obscure detail, but it illustrates the delight anyone who plays or watches the New Jersey political game can take in a movie chock full of familiar faces, places and, yes, web sites.

Besides Booker and Sharpe James themselves, there's Jim McGreevey, practically dancing behind a podium as he exhorts a tent full of the mayor's supporters to pound the pavement on behalf "the real deal," while Newark and Essex County leaders look on.

There's also Bill Bradley, lending support to Booker after James has accused his challenger of being funded by Republicans.

And, in the scene that generated the loudest audience response at Sunday afternoon's screening, there's Rich McGrath, the state Democratic spokesman who worked for James in '02, stammering his way through a soul-searching monologue— it seems unlikely he knew he was being filmed— confessing that he wished he'd gotten to know James before taking the job and branding the campaign's press operation "idiotic."

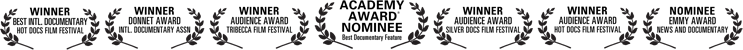

But to watch Street Fight only for the chance to say "I know that guy!" or "I've been to that place!" is to shortchange a truly exceptional piece of film-making. First-time director Marshall Curry spent nearly three years condensing 300 hours of raw footage into a tight and coherent narrative that has universal appeal. Indeed, it was announced before Sunday's screening that the film was the audience's pick as the festival's best, netting Curry $25,000.

One could argue that Curry stumbled into a gold mine when he ventured from his Brooklyn home to Newark, but not anyone could have taken such a complicated and colorful campaign and produced something this focused and, dare I say, sharp.

Central to Street Fight is the age-old clash between a reform-minded outsider and a cagey guardian of the establishment. But with Booker's golden boy resume— Stanford athlete, Rhodes Scholar, Yale law degree— and James's ruthless exploitation of his grip on the city's political and business world, there's no better setting to explore it.

We see the power of incumbency, big city-style. Booker billboards are blotted out and police officers are secretly recorded tearing his signs down and stomping on them. A business owner returns his lawn sign to Booker's campaign, explaining that the mayor's police force paid him a visit and suggested his city contract was at risk.

Meanwhile Booker, branded Jewish, gay and insufficiently black by James, retreats across the Hudson to raise money from wealthy and sympathetic Manhattan liberals. He also appears on a New York hip hop radio station to reassure an exercised disc jockey that he is not a Republican, as James has accused him of being.

Unlike James, Booker gave Curry virtually unfettered access— there is a scene in which he locks the director out of a crucial meeting— but the movie reveals more about the mayor than Booker.

Curry was attracted to the project after meeting Booker in person and coming away convinced the hype— Time once asked if Booker could be the savior of Newark— was real. To James, who trusts almost no one to begin with, this made the director an enemy.

So Curry shows up at the mayor's campaign announcement and, upon being spotted by James, is ushered out by a hyper-aggressive team of police officers who demand identification (Curry gives it to them) and his tape (he refuses.) Weeks later, Curry catches up with James in the Ironbound, where the high-energy mayor jokes to the crowd that he had too much wine before his speech. Afterwards, a beaming James, poised to kiss an infant, spots Curry and drops his smile, instructing his aides not to let the documentarian film him.

Later, Curry gets around his persona non grata status by enlisting a cameraman friend, who sneaks onto a bus full of field workers who take turns telling the camera that they've been imported from Philadelphia to assist James— for cash. Moments later, James boasts about his "volunteers" to reporters.

It's easy to walk away seeing James as duplicitous, an opinion many people have of him already. But this is a man from the streets of one of the toughest towns in America. He knows how unfair life is. Why should he play fair and risk losing his city to someone who grew up in suburbia?

Booker is on camera more than James, always, it seems, in total control of his composure. He's a vegetarian who doesn't smoke or drink, we're told, and even as he's confronted by hostile residents who have bought into the James attacks, Booker remains relentlessly upbeat and optimistic.

We visit Booker several times in his cramped apartment, which is in Brick Towers, a low-income project in the Central Ward. He unwinds by lifting weights or hitting his punching bag but the comfort and intimacy of being at home doesn't prompt him to say anything particularly revealing; we get the sense there's a more authentic Cory Booker not willing to show his face.

One of the reasons Booker has been pegged a future White House prospect his media-savvy, so it's not inconceivable that he was playing to the camera— like when he tersely rejects an aide's advice that he prepare glib sound bites for a debate.

In his public comments, Curry seems sensitive to the perception that his film is little more than an 82-minute Booker for Mayor infomercial (he may not have helped his cause by choosing to end with a close-up shot of a Booker 2006 sign.) In the film, he takes pains to credit James with reviving the city's downtown, and when we see the mayor giddily joining a group of women to dance what looks like the Electric Slide, we understand his personal popularity.

Much attention is paid— with justification— to James's more devious tactics, but Curry doesn't examine a far more legitimate concern about Booker— that he might have his eyes on a prize bigger than city hall.

At one point, Dr. Cornell West, the Princeton academic and author of Race Matters, pops in to Newark to endorse Booker. Standing on stage with Booker before throng of adoring supporters, West tells the candidate that "this is just the beginning for you." It's meant as a compliment, but Booker seems uncomfortable— and camera-conscious— upon hearing it. He's never questioned about it, though.

Sunday was the third and final Tribeca screening for Street Fight, which will be broadcast nationally on July 5, part of the PBS series P.O.V. The audience at the Battery Park 11 included a number of Newark residents, not to mention Booker himself. But most attendees seemed to be the film-literate, non-political-types you'd expect at such an event.

When he showed up on screen, McGreevey was greeted with laughter, likely known to the audience only as that New Jersey governor who resigned in disgrace. And there were audible gasps throughout the film as the strong-arming of the James machine was documented. When it was revealed that James won the election, one woman exclaimed, "Oh my God!" and another approached a Booker aide afterwards and asked if she could donate money.

Back to Press

© 2012 Marshall Curry Productions. All rights reserved.